“For the love of God, not one more thing!”

This was my first thought when hearing about the Environmental Principles & Concepts (EP&Cs) roughly three years into my Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) journey. After much struggle and frustration I was by no means an expert, but was just beginning to feel like I had somewhat of a handle on the alphabet soup of DCIs, SEPs, and CCCs. It was then and there at the Ventura County Office of Education’s NGSS Rollout Three that I decided I would ignore this new box on my NGSS graphic organizer because it was just too overwhelming.

I’m slightly embarrassed by this reaction, but bring it up because I don’t think I’m alone in feeling this way with new initiatives in education, no matter how amazing or beneficial they are. It’s important to recognize how teachers feel when introduced to new information (just like our students). My plan was not to ignore it forever, but my self-consciousness about my reaction helped me to educate others when it was time.

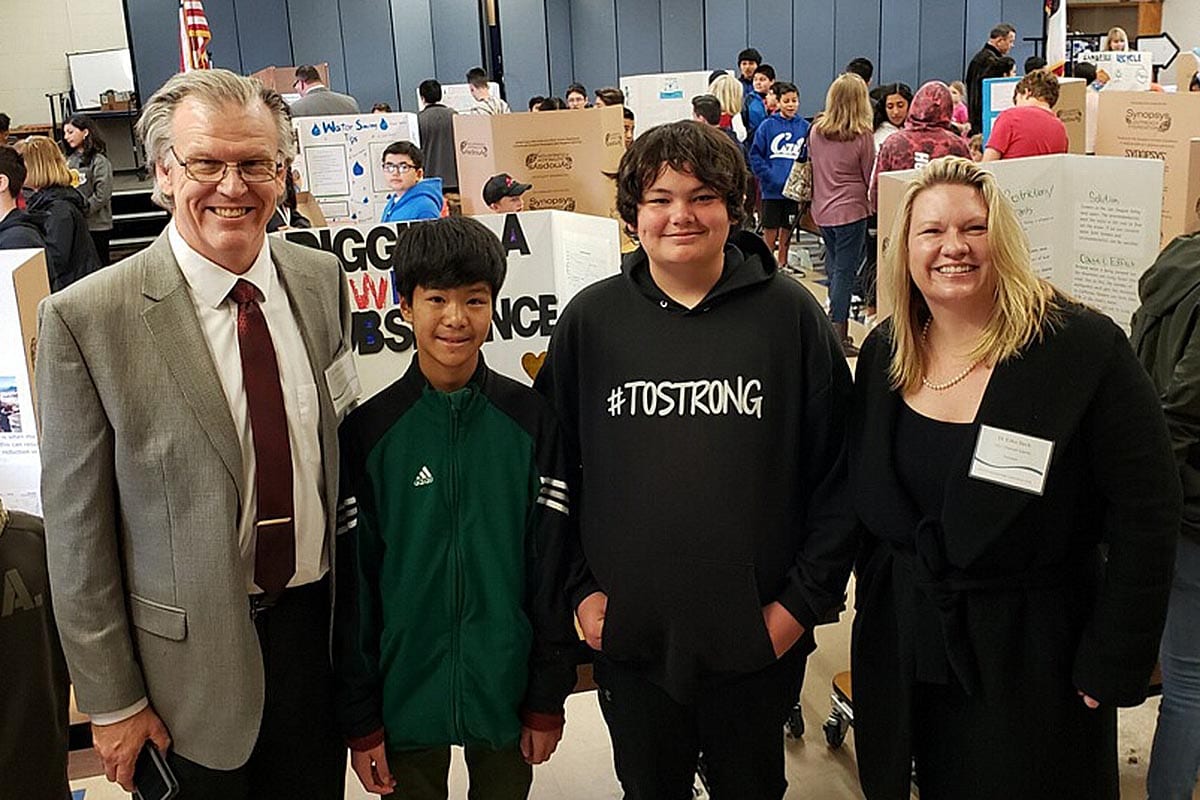

Dr. Phil Hampton, director of the Ventura County STEM network, and Dr. Erica Beck, president of California State University Channel Islands (CSUCI), with two middle school students

About five months later, I started seeking out people who were more comfortable and knowledgeable with regards to environmental education. I also decided to theme my summer institute, the Ventura County STEMposium, around the EP&Cs to force my own education and to take advantage of the learning opportunity for myself as well as the institute’s participants. With the help of NatureBridge, Channel Islands National Park Service, the CSUCI Environmental Studies Program, and California Regional Environmental Education Community (CREEC), I was able to introduce over 75 teachers to the world of environmental education. I had spent that school year experimenting with using local, place-based environmental phenomena to introduce 5E lesson sequences and weaving existing lessons into meaningful storylines. I began to see, through my students’ experiences that the EP&Cs and environmental literacy were actually making my life easier. It was the missing link I had been looking for to completely integrate my lessons together with purpose and relevance for my students. I went from teaching kids about science to facilitating student advocacy.

This experience led to a middle school environmental conference, and a continued commitment to make the EP&Cs a central focus in my summer institute. Since I began my position as a science coach, it has been my goal to hold a middle school science fair that involved all middle school students. I worked with my middle school science department for five years to implement this project to the best of our ability, and we facilitated some significant breakthroughs and meaningful moments for students—several of our students went on to compete in larger science fairs with great success.

However, there were also a significant number of students and families that were growing to resent this project and, as a result, science in general. Many kids were uninspired and simply checking the boxes to get this project done and receive credit. Discovering the world of environmental literacy provided an avenue out of this rut. Instead of running a schoolwide program that took away from NGSS standards, we now had a way to blend content with student advocacy: students thrive when they have pathways to contribute to our world.

Middle school students are desperately searching for ways to be seen as independent people who have something to offer the world. It is the perfect time to introduce them to issues they actually have the ability to contribute to change.

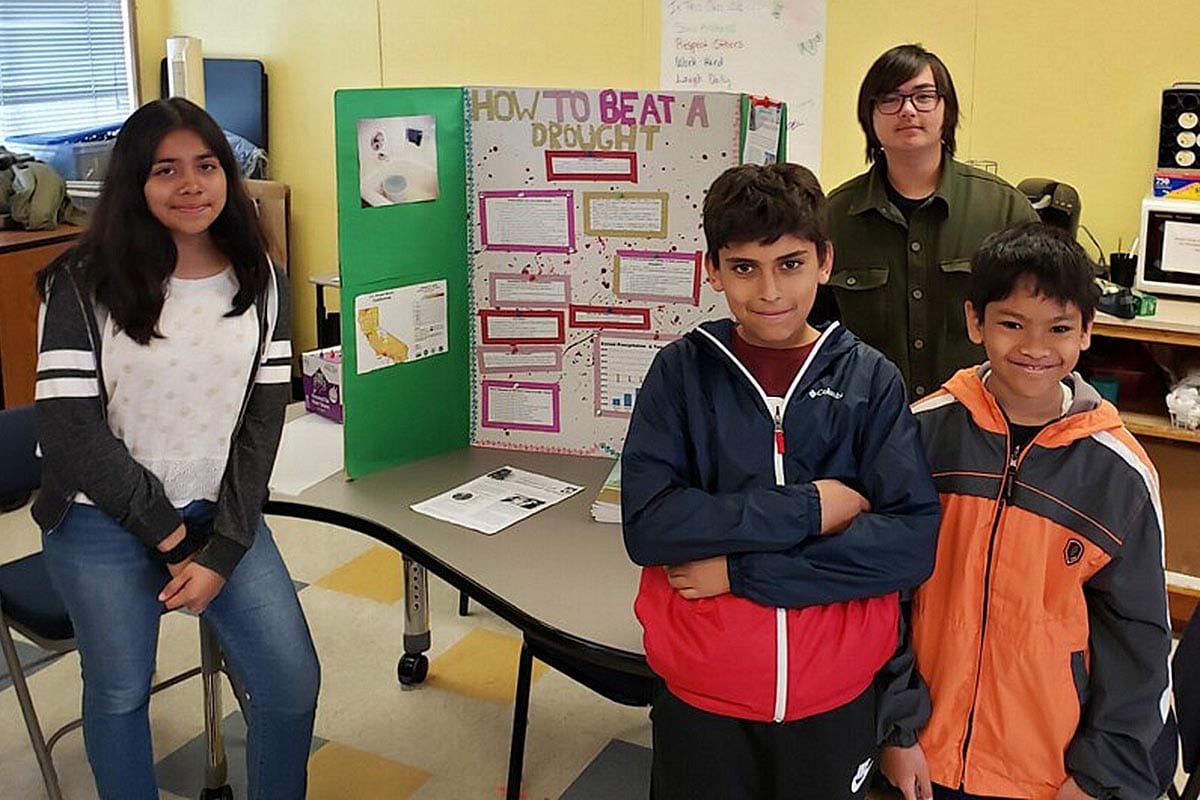

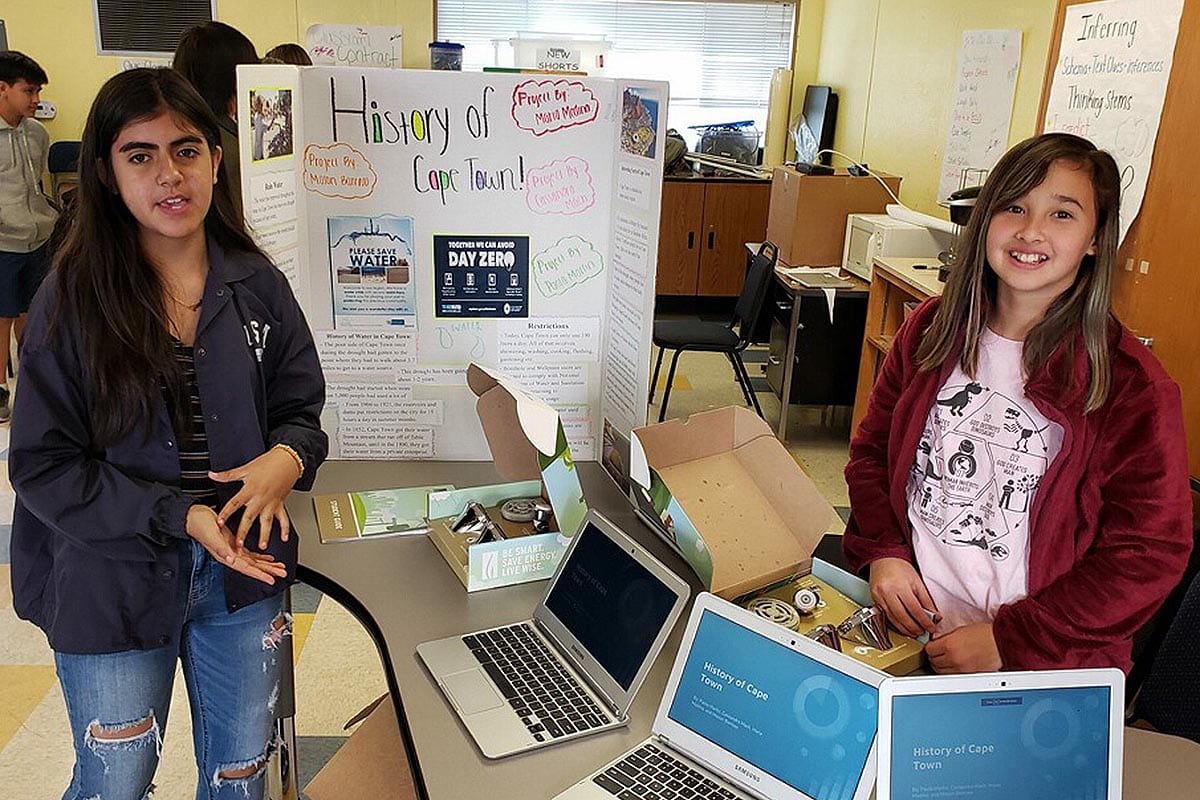

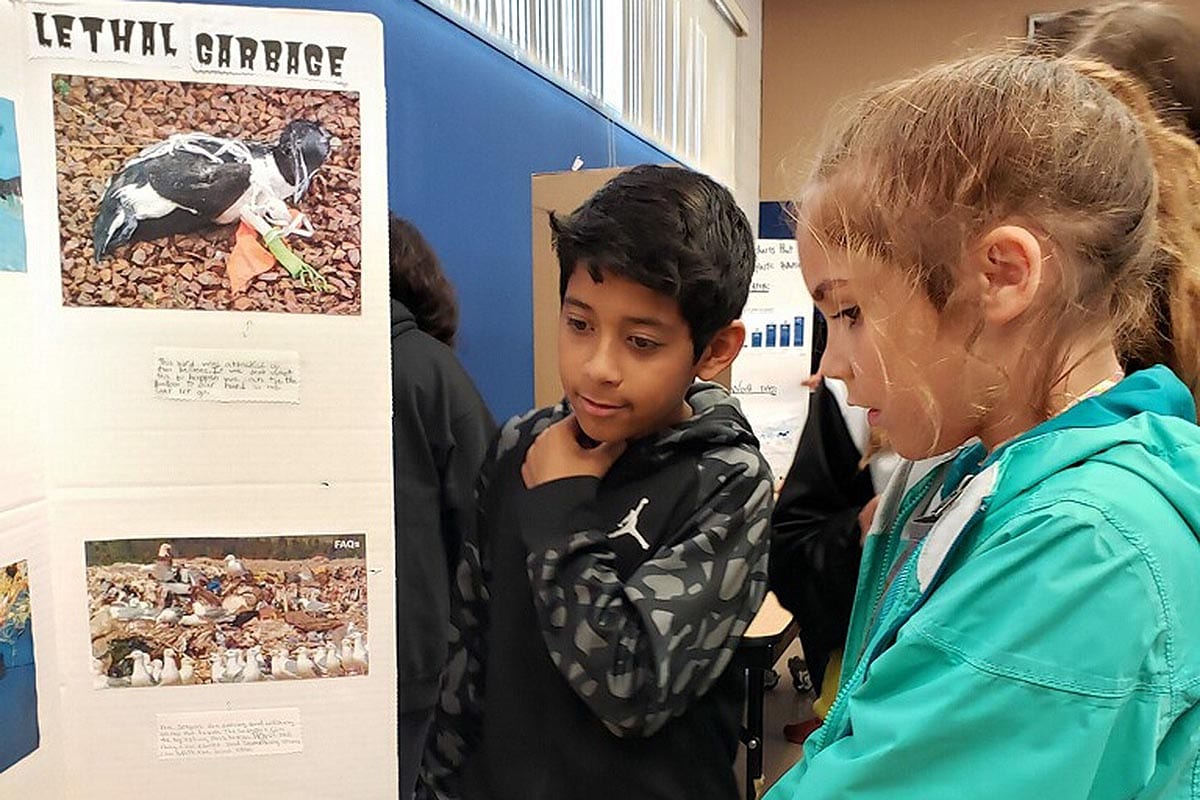

Additionally, that these topics were integrated into NGSS standards brought my teachers onboard in a genuine way for the first time. This project was making their lives easier because they didn’t have to organize a project in addition to what they already had to do. It wasn’t the dreaded one more thing. As a department, we decided to focus our projects around the human impact standards and bundle them with other performance expectations for each grade level: sixth grade focused on ocean plastic pollution, seventh grade on water distribution and overuse, and eighth grade on human overpopulation. After experiencing a lesson sequence based on a local environmental issue, each class broke into groups of four that presented different areas of the problem: education, solutions, and initiatives.

The students created interactive stations around these themes that were presented to parents, teachers, elementary students, board members, and university and community partners. At each station, conference goers had the opportunity to interact with the different student groups by playing a trash sorting game, having students analyze their water footprint, hearing about the most and least littered areas of our campus, viewing vertical garden designs, learning about how Capetown’s water conservation protocols kept them from running out of water, discussing how to reduce single-use plastic products, and so much more.

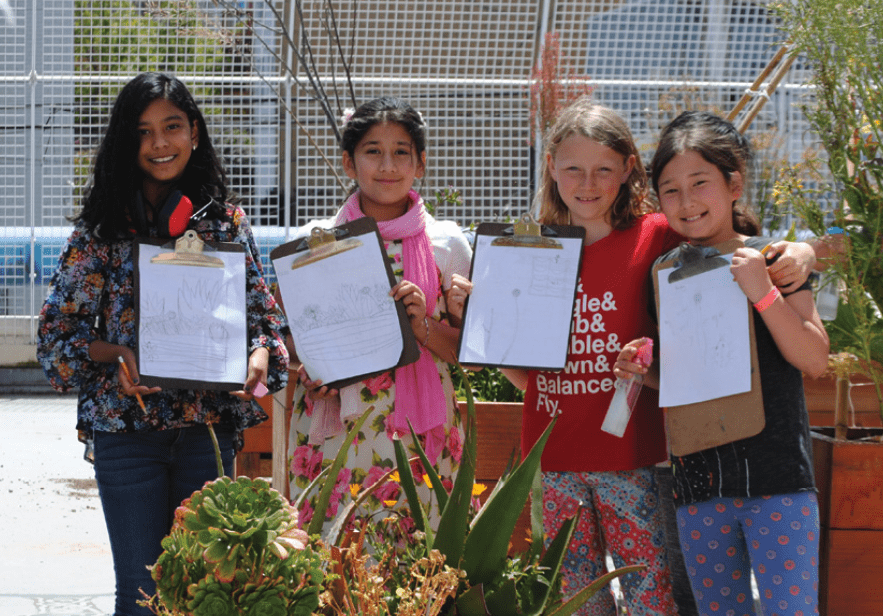

Because our school is the professional development school for CSUCI, we were able to partner with one of their organizations, VC STEM, to bring their Junior Scientist Program to our campus. VC STEM provided undergraduate students and professors to partner with our sixth grade teachers and students in a trash assessment survey in line with California requirements for waste management. By the end of 2020, all academic institutions will have to have a plan in place to monitor and reduce their waste that ends up in storm drains.

With VC STEM as a partner, students were able to develop the protocols and solutions for their own campus.

The students sectioned off the campus into zones and monitored the amount and type of trash. They noticed that the ratio of trash cans to students was too low, and that the trash cans were not placed in the most effective places. As their final action-oriented project, student groups focused on creating a website that empowered other schools to:

- Assess their trash;

- Run campaigns to get filtered water dispensers on campus to discourage the use of single-use plastic bottles;

- Begin a green team or environmental club;

- Start a marker recycling program;

- Increase the number and efficiency of recycling systems on campus; and

- Run an anti-littering campaign.

Students presented their ideas at an environmental conference to other students, teachers, parents, community stakeholders, and our school board. Some of our student groups—representing special education students, English language learners, and students who can be quite disengaged on a regular basis—were invited to the CSUCI SAGE conference to speak about their experience. This research conference is an opportunity for CSUCI undergraduate and graduate students to showcase their work with posters, oral presentations and some displays.

Our school board and teachers were especially impressed, and one teacher was moved to tears as he watched a student who has experienced great academic and personal struggles eloquently speak to the chancellor about global population trends impacting our environment.

Adding in the environmental component to my science repertoire has been like stringing a beaded necklace. I had all the beads before (the hands-on component, the conversations, the collaborative group work, etc.), and was even able to place them in the right order—but I had nothing to keep them together or tie the end to the beginning.

For longer than I’d like to admit, I let excuses such as the inconvenience of field trips, or the potential chaos of taking kids outside, or the unknowns in reaching out to community partners keep me from being open to this amazing facet of science education. Fortunately for my students, myself, and my colleagues, I was very wrong about environmental education being one more box to check off during the day. I still have a lot to learn and am a big fan of baby steps but I have found that my most impactful lessons with the highest student engagement are driven by local environmental phenomena. My students no longer ask, “why are we learning this?” Now they ask, “what can we do about this?”