This Is Environmental Literacy: Plumas County

It’s a dark November night as I drive through the western Sierras toward Quincy, CA (elevation 3,423 ft.). The narrow road twists through pine and rock as the elevation rises, edged by water spanned by erector-set bridges and intermittent power stations. Because it is so dark, because there are no streetlights, and because the stars are hidden by the mist, the landscape is implied by the space that is not taken up. I can’t resist crossing a one-lane bridge across the Feather River into Belden, even though it’s dark and everything is shut down. It is a place I will be visiting again in two days, although I don’t know it at the time. I also don’t yet know that the roads I am traveling are laid directly over trails made by the Mountain Maidu long, long ago.

The town of Quincy is just as quiet as one would expect a remote mountain town to be on a Sunday night at 8pm. I stop into Moon’s, a restaurant whose rough-hewn exterior implies a warm interior. The fire in the wood stove, coats and hats hanging on a communal rack next to the front door, and patrons conversing across the dining room fulfill that promise, and I realize that I am in a place that exists based on a tangible sense of community. I am here at the invitation of Rob Wade. Rob’s professional CV reads something like this: Coordinator of the Plumas County Unified School District’s Outdoor Education Program; award-winning educator specializing in place-based learning in the Feather River Watershed; founding member of the Feather River Land Trust; Coordinator of the Trust’s conservation and education program, Learning Landscapes; Director of the Feather River Outdoor School.

Yet with all that, it still doesn’t quite get it said. What begins to, though, is Rachel, the young woman who brought me my (excellent) meal. We exchange pleasantries as I settle the bill, and I tell her I’m here to meet Rob and some of the students, teachers, and administrators of Plumas USD. Her face breaks into a wide smile as she begins to enthusiastically sing Rob’s praises, and shares memories of her own experiences in the monumental 6th grade rite-of-passage outdoor experience that all Plumas USD students access. “Rob is awesome! He does such great work with the kids. He took my 6th grade class on outdoor ed. It’s something every kid looks forward to here.” She talks about the impact the experience had on her, and while she’s speaking she exudes a sense of pride in being a Mountain Kid; I’m about to understand why.

My next 48 hours in Plumas County provides many deep and powerful lessons on the meaning of place, of place-based learning, of public education and the public trust, and of community.

PLACE: HISTORY

Quincy sits on the south edge of the American Valley in central Plumas County, against the western slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range. It is the county seat, population ~5,000. Plumas gets its name from the Spanish name for the Feather River (Río de las Plumas), which flows through the county. Quincy made its debut alongside the birth of the county on March 18, 1854, when an act was passed by the State of California creating Plumas County from the eastern portion of Butte County. Predating Quincy, this place has been (and continues to be) the home of the Feather River and the Maidu people. The Maidu have always been here; Seeloom is the original name of this place.

Emigration to Quincy was based on the gold rush. In 1850, African American frontiersman James Beckwourth’s discovery of the lowest pass through the Sierras blazed a trail that enabled much of the migration to the area. Originally a Native American path through the mountains, Beckwourth was credited with discovering what came to be called Beckwourth Pass, a low-elevation pass through the Sierras. In 1851, he improved what is now known as the Beckwourth Trail. It began near Pyramid Lake and the Truckee Meadows east of the mountains, climbed to the pass named for him, traveled along a ridge and between two forks of the Feather River before passing down through the gold fields of northern California ending in the Sacramento Valley. The trail spared emigrants about 150 miles, several steep grades, and dangerous passes (including the infamous Donner Pass) as they made their way west.

Significant numbers of Chinese miners settled in the area and built roads, ditches, and other infrastructure. During the 1870s the area was in full economic boom, and while the 1900s saw the decline of mining, the timber industry began to rise. By 1910, the Western Pacific Railroad connected Quincy with the rest of the world. With gold and copper mining still active, the timber industry’s rapid development, and the American Valley’s steady agricultural output, Quincy thrived. The upswing in the timber industry translated to new mill business and migration to the area. Quincy Lumber employed hundreds of men, many of whom were African American migrants from Louisiana and Arkansas. In 1940, African Americans in Quincy comprised 40% of the town’s population, and although the mill closed many years ago, former employees remained, raised families, attended local schools, and became a part of the community. In some ways, this place (and the way people connected to and in it) translated to Quincy being ahead of the nation:

‘Though segregated housing was the norm, little else was divided by race. After two years of resistance from white locals, African American children began attending local schools in 1940. Their presence generated [for the time and place] scenes of remarkable integration. In fact, by the Spring of 1954 a black senior, John Clark, was elected student body president at Quincy High School. White adults entertained at “the Sump,” a black club in the Quincy Hotel. Local African Americans often spent their leisure hours in the Quarters at B&B’s Club owned by Ben and Alberta Conston. A white Louisiana native remarked on the degree of integration in Quincy and Sloat saying openly what many black and white residents already knew: that such intermingling would not have been possible in Lake Charles, Louisiana. While the introduction of hundreds of African Americans into Sloat and Quincy was not without problems, the white and black citizens achieved degrees of integration rarely seen in other parts of the United States at that time. Economic benefits bound black and white workers to the Quincy Lumber Company and the company with the community.’ (Crawford, 2006)

This awareness of the interdependence between a community of people and nature has history here, an unbroken narrative. It is not a new idea; it transcends politics, individual ideologies, ethnic, racial, and cultural differences, and in a place like this we are able to see how deep roots grow strong trees.

PLACE: SYSTEMS

Understanding and honoring the interconnectedness of people and place is expressing itself in innovative and essential ways in Plumas County. Notably, through the K–12 public school system.

Having entered the mountain ecosystem the night before, I meet Rob Wade early the next morning at a local cafe and quickly find myself entering what could be rightly called a sub-system—one that is defined by the land, and exists to ensure the ongoing success of the land and the people who inhabit it. Sitting at a long table in a corner, I immediately know when Rob walks in. Not because I recognize his face (I’d never even seen a photo), but because everyone in the cafe greets him in turn as he makes his way to the counter. Like he’s the mayor, only everyone genuinely likes him. Our first meeting is set to go quickly, as we’re due at the first of three student outings (in the next 24 hours!) soon. In that hour in the cafe I understand why Rob inspires the reaction I’ve witnessed: he is the most Zen air traffic controller imaginable, the hub of a wheel whose spokes represent a stellium of partners who would not be functioning with as much coordination and impact without him.

In 1995 Rob stepped into a role as Director of the Outdoor Education Camp, already a program within Plumas USD. In the early 1980s former Curriculum and Instruction Director of Plumas USD, Joe Hagwood, approached former District Superintendent John Malarkey, hoping to start an outdoor education program. What Hagwood recognized and wanted to address was a lack of connection between kids and their natural surroundings. “There was a belief at the time that because kids lived in the mountains, they intrinsically knew everything about the natural world around them. This was far from the truth. In order to care about something, students need to have a basic understanding of it. So, we set out to create a program for kids to learn about the forests, creeks, and meadows around them and in the process, forge a connection to the land and their home.” Hagwood approached Warren Grandall, the Public Affairs Officer with the Plumas National Forest Service and John Gallagher, the Outdoor Recreation and Leadership Director at Feather River College with his ideas, and the three collaborated to create a basic framework and curriculum for the camp. In partnership with the Plumas National Forest Service and Feather River College students, the camp had professionals volunteering to staff the camp.

What started as a two-day, one-night overnight camp for the local 6th grade class in 1988 has grown into a countywide, comprehensive set of K–12 experiences integrating outdoor and classroom education, Next Generation Science Standards, districtwide teacher professional learning, outdoor classrooms accessible to every school site, and partnerships that include many more stakeholders than the original three. And at the center of this galaxy, Rob Wade’s soft-spoken commitment and passion is the gravity.

In October 2017, Plumas Unified School District (USD) invited the entire Plumas County community to the historic Quincy schoolhouse in celebration of 30 consecutive years of outdoor education for K–12 students. How did a two-day, one-night overnight camp for a handful of 6th grade students (at what was then known as the Outdoor Education Camp) evolve into a four-day, three-night centerpiece experience that all Plumas USD 6th graders participate in? And perhaps an even bigger question: how did this evolve into the Feather River Outdoor School and Outdoor Core program—a districtwide commitment to provide environmental education to every K–12 student? The short answer is shared commitment to people and place. Nurturing, sustaining, and growing that commitment is a deeper story.

PEOPLE + PLACE: GROUNDWORK

Long before California’s Blueprint for Environmental Literacy, Joe Hagwood, John Malarkey, Warren Grandall, and John Gallagher inherently understood not only the power and necessity of collaboration and partnership, but also how connection to place is integral for all learning, and supports K–12 learning across core subject areas. As Hagwood noted at the 30-year celebration, “Rob has a knowledge of the outdoors, but more importantly, a knowledge of how to transmit that to students in an outstanding way. Things change, but the one thing that has remained solid is that we could not have dreamed what Rob would do with this program.”

Before introducing some of the moving parts of the aforementioned program, it’s helpful and appropriate to note that the original three collaborators (Plumas USD, Plumas National Forest Service, and Feather River College) have company. Rob refers to them throughout our conversations, naturally and as if they are names of the teachers and students he is so familiar with. They now include Feather River Land Trust and the Plumas Corporation, as well as intersections with US Fish and Game, Roundhouse Council, Plumas Arts, and the Sierra Institute.

PEOPLE + PLACE: SUSTAINING

In very essential and practical ways, place and culture are inseparable. Whether this basic truth is ignored or accepted is variable. In Quincy, and Plumas, this interrelatedness is highlighted. It lives right out front. Case in point: I first meet many folks from Rob’s organizational partners one evening at the district building, convened not around outdoor or environmental education, but to save the historic Quincy schoolhouse building. During my time here I frequently have the uncanny sense that California’s Environmental Principles and Concepts (EP&Cs) are alive and present in the most unobtrusive and natural sense. There is a palpable feeling of shared agreement that when care and respect are given—to the land, to its resources, to its people—there is a reciprocity that flows from actions informed by that ethic and returned to the system, keeping it healthy and ensuring success. And as this is part of the culture here, evidence of it can be seen in the way its people build and sustain their structures.

Plumas USD and its partners, guided by Rob’s inclusive vision and direction, have chosen to acknowledge and elevate that cultural value. Below are the nuts-and-bolts of the Outdoor Core district science strategy which Rob has built at Plumas USD. I want to stress that this is districtwide—meaning every school, every teacher, every student accesses and receives the benefits of:

- Paid teacher professional learning in Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) using California’s EP&Cs & Blueprint for Environmental Literacy at least two times each year

- K–12 EEI Curriculum training and materials

- Learning Landscapes outdoor classrooms located within a 10-minute walking distance to every school site countywide (Feather River Land Trust partnership)

- Regular monthly outdoor learning for all students (with some teachers implementing up to three times per week)

- Grades 3–12 restoration trips (US Forest Service, Roundhouse Council, Sierra Institute partnership)

- 6th grade Plumas to Pacific year-long watershed experience (Plumas Corporation partnership)

- Opportunities for youth leadership & mentoring at upper-grade levels; e.g., high school students trained to lead field trips and mentor younger students (Feather River Community College partnership)

Each one of these bullet-points rightly deserves its own blog post, as do the partners who do their part to ensure the Outdoor Core experiences integrate with classroom learning. But Plumas is just too beautiful to stay inside, so in the next section we’ll see what coordination of the above elements looks like over the course of two days in the world outside.

PEOPLE + PLACE: GROWING

Two days = One NGSS teacher professional learning session, one elementary school trip, one middle school trip, one Plumas to Pacific trip, one community meeting, and five interviews with some of Rob’s collaborative partners. Powered by trees, the Feather River, and fresh mountain air (and a steady intake of maté).

1.1: Koyom Bukum Sewinom Bo

It’s a sharp 28º when I meet Rob at a small dirt lot in the Plumas Forest about 30 minutes outside of Quincy. We chat for a bit while waiting for a group of middle school students to arrive for a morning of observing the river ecosystem for their science journals, which they add to all year in a variety of settings. I can hear the river, and can’t resist the pull toward it. At the trailhead I see a sign that evidences Plumas National Forest Service education liaison Michele Jimenez-Holtz’s collaboration with the Maidu Roundhouse Council. It reads:

Koyom Bukum Sewinom Bo

(Valley End Falls Trail)

Today the falls are commonly called

INDIAN FALLS

Let the sound of the thundering water carry you along this 600-foot trail to what is called in ancient Maidu ‘Koyom Bukum Sewinom Bo’, meaning Valley End Falls. As it has been for countless generations, the waterfall is still culturally and spiritually significant to the Maidu Indians.

Today, the area provides visitors a place for recreational and spiritual experiences. Please respect the rights of others. Enjoy yourself on your journey as you recreate or focus on the past.

I ask the reader to pause here for a moment, and consider the intentionality of the above, and how it engages visitors and contextualizes this place immediately upon arrival. Countless generations. Culturally and spiritually significant. Respect. Journey. Each sign along the trail includes Maidu names and refers to the current and historical significance of each part in this ecosystem.

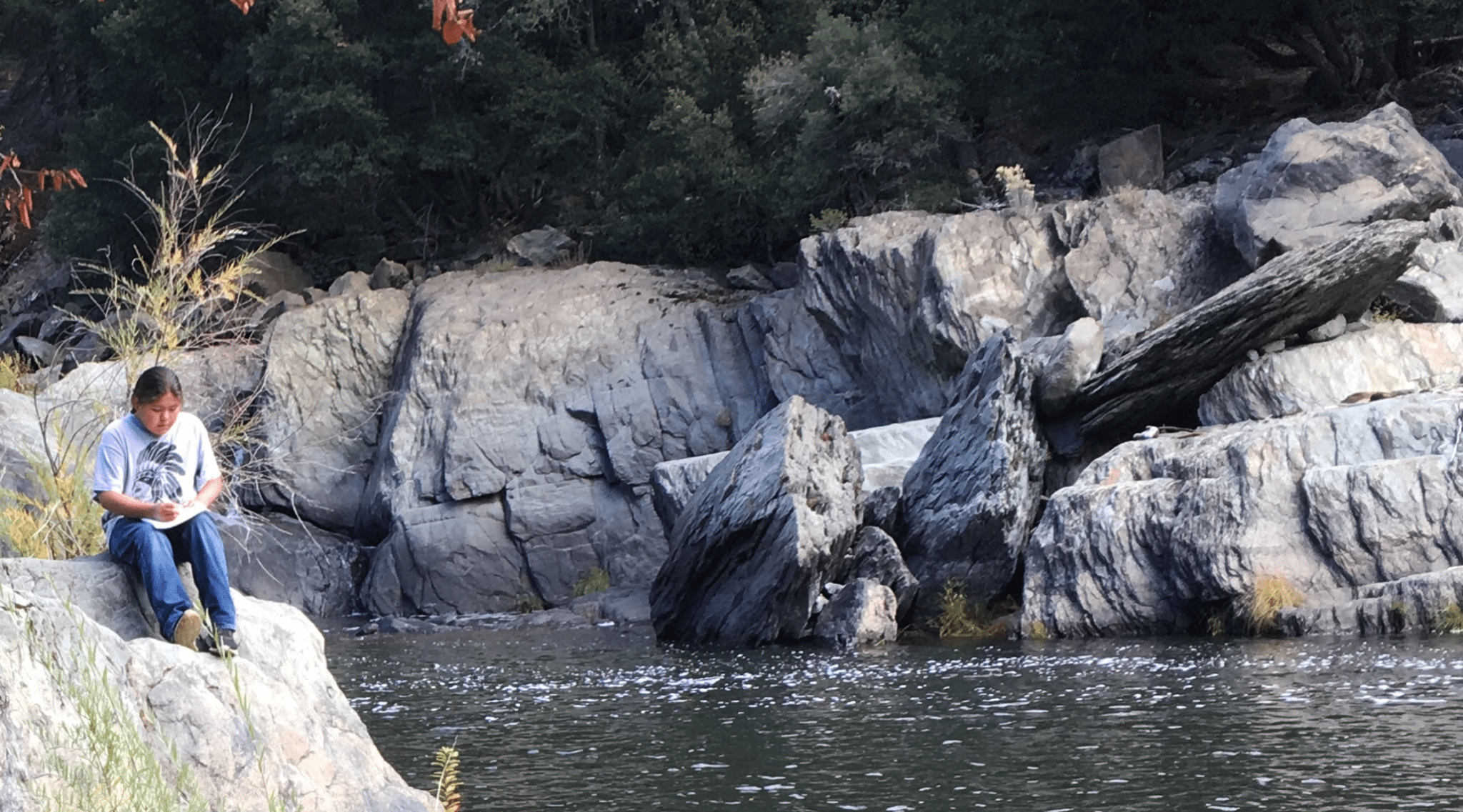

Did I mention it’s cold? Hailing from Chicago and the Northeast, I don’t mind, plus I’ve got old-school layers (i.e., wool & leather). As the middle school students exit the bus, I see the proud Mountain Kid ethic crossed with the singular awesomeness of 12- and 13-year-old folks: sweatshirts (or not!) and sneakers. Maybe a few hats. Zero gloves. Rob is on a first-name basis with all of them; this is consistent throughout all the outings I have the good fortune to go on. These kids are composed—at first I think maybe it’s the early morning bus ride, but as we head down the trail I understand it’s something else. Regular exposure to scientific practices, both in the classroom in preparation and applied to outdoor learning. They are engaged and enthusiastic, but not out of control. This is so much a part of their formal learning experience that they arrive down at the river at their own pace, respectful of the forest without exception. They stop and record observations in their journals and interact with their surroundings with no prompting from the adults, who are also completely relaxed. I think about other student outdoor experiences I’ve witnessed; the frequent control and correction issued forth from adults, kids excitedly running roughshod over pretty much everything, sensing the fear the adults feel around them approaching features of the environment. Rob’s Mountain Kids are free to wander along the trees, rocks, and banks of a very cold, fast-moving mountain river. To interact, observe, touch, discuss, or sit and reflect as they record their experiences here. This is a result of the work that he and the teachers and staff of Plumas USD have implemented and committed to as an expression of a culture that interweaves academic achievement with valuing people and place.

1.2: Belden Town

We part ways with the middle school group and meet 30 minutes later just across the road from the one-lane bridge to Belden that I crossed in the dark on Sunday night. We are waiting for a busload of elementary students from several classes to arrive at the foot of a PG&E hydroelectric installation, the Eby Stamp Mill, and US Forest Service restrooms. Belden has an interesting story; it is named for Susan Belden, a Maidu woman married to a miner and settler named Charles Belden. The once-successful mining town shared the spotlight with the railroad while the most rugged Trans Sierra line in California was built before falling into disuse. In the early 1980s, Ivan Coffman left urban living behind and purchased the town. It’s now an eclectic resort with a lodge—complete with artifacts from mining days, Maidu creations, pool and ping pong tables, a multitude of family board games, and a gigantic wood-burning stove— and restaurant, formidable old bar, and several cabins and camping accommodations. In the summer, it is a destination for small indy music festivals and summer vacationers. During the school year, Ivan makes the town available free of charge to the students of Plumas County for outdoor learning based on its natural and historical features.

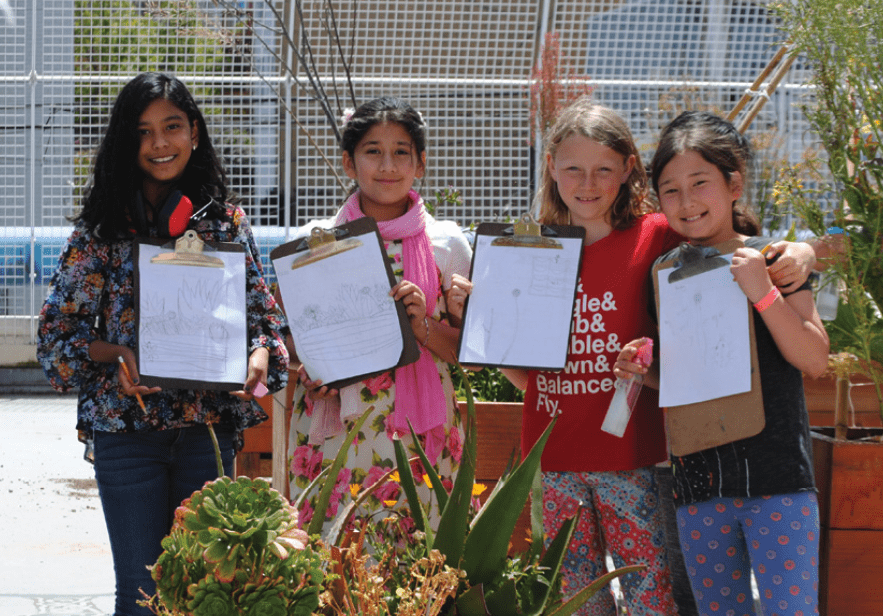

As I’m talking with Rob and Max Egloff, Quincy native and adult Mountain Kid who often supports Rob with Outdoor Core activities, the bus pulls up. Kids and parents stream out rapidly; apparently there’s been a de rigeur puking-on-the-twisty-road incident. After everyone has a chance to use the facilities, the kids get on the bus to cross the one-lane bridge spanning the river into Belden. Max has recently come back to Plumas after living in Hawaii, and I can see why. The cold, misty morning has turned into an incredibly clear, sunny afternoon. Walking across the bridge in the afternoon light, I realize why I hate high-definition television; I’m seeing the real thing, that effect which technology seeks to imitate but can never recreate. The elementary students have several parent and grandparent chaperones, so that smaller groups can explore without jamming each other up while discovering the answers to their scavenger hunt activity. Although this group is three times as large as the middle school group and the students are younger, I observe the same patience, engagement with, and respect for their surroundings. This includes the way they interact with the physical landscape, adults, and each other. Of course there is excited charging ahead and a mixture of personalities from silly to serious, but they are all comfortable and encouraged to explore, discover, observe, reflect, hypothesize, and draw conclusions. And they are very good at it.

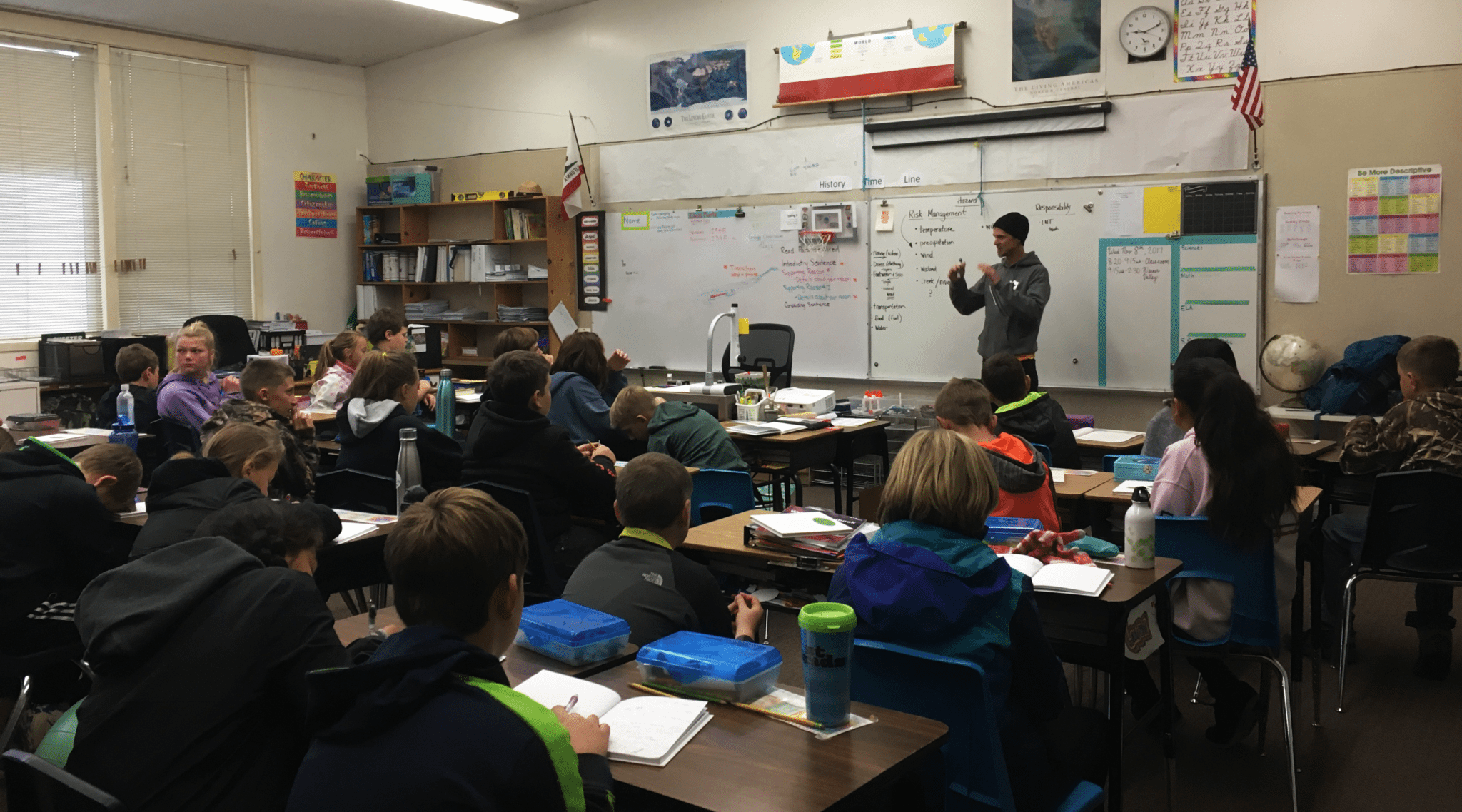

2: Headwaters

Bright and early the following morning, I drive about 45 minutes out of Quincy to another Plumas USD school site. I’m escorted to a classroom where Rob and high school youth leaders are preparing the school’s 6th grade students for the day at Lassen Volcanic National Park. This will be their first trip to the headwaters of the Feather River’s North Fork; by the end of the school year they will have followed the path of the river, on foot or by travelling on the water itself, all the way to the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the San Francisco Bay. Standing at the back of the room, listening to Rob speak to students about applying critical thinking skills to risk management strategies based on real-time observations out in the field, I am again struck by the evidence of just how much student capacity for learning is impacted by the adults in their educational system. The presentation is not ‘dumbed down’. The teachers and students do not look vacant, alarmed, or confused as the potential for snow, freezing rain, uncrossable junctures, and encounters with wildlife (including bears) is discussed. Outside Rob asks if I’d like to ride the bus to Lassen. Remembering yesterday’s bus arrival at Belden, and conscious of my impending drive back to the Bay Area, I politely decline. It turns out that the bus is at capacity, and I end up driving Rob up the mountain. I did not record our conversation as we drove through the light sleet that was falling; some part of me wishes I had, but another part appreciates that the specifics remain in that time and place. Suffice it to say it was a profound conversation about place, about the connections between the earth and its inhabitants, about our responsibilities around upholding the promise of public education and the public trust, and that if I could clone Rob Wade without it being an affront to natural law this would be a much kinder, gentler world.

The sleety rain continued as the students and teachers disembarked from the bus at the peak. Rob took a hands-off approach, and had the high school student leaders run the day’s activities as we set off on one side of the river, with Rob mostly parallel across on the opposite side. I walked for a while through the snow with one of the teachers, who spoke for 20 solid minutes about the Outdoor Core program. She detailed the impact the regular, well-planned professional learning has had on her and her ability to teach science in and out of the classroom with confidence; how the EEI Curriculum and trainings have been an invaluable resource for her, her colleagues, and students; how Plumas USD and community support have elevated and put student-centered and place-based learning front-and-center; and how she felt proud and valued as an educator in Plumas County.

As I broke off from the group and turned to head back to the peak, Rob and I made eye contact and exchanged a wave. Upriver alone in the snow, I knelt beside the beginning of the North Fork of the Feather River and offered my own prayer of gratitude. Its life-giving waters filled the steel canteen Rob had given me as a gift; it says Mountain Kid, and in just two-and-a-half days in Plumas County I understand why that rightfully engenders such a deep sense of pride.

[Much respect and gratitude to: Rob Wade, Michele Jiminez-Holtz (Plumas US Forest Service), Max Egloff (Plumas USD), Rick Stock (Feather River Community College), John Sheehan (Plumas Corporation), Ivan Coffman, the teachers, staff, and students at Plumas USD, and everyone else who shared their time, knowledge, and hospitality.]