Breaking out of and into oneself simultaneously characterizes the turbulent nature of youth. The limits of the relationship between oneself, others, and the world speak most loudly in our doubt and mistakes. Coming into oneself means testing the boundaries of possibility and inevitably going through disequilibrium. Youth reminds us of the curiosity and awe that lay the foundation of science-based inquiry. Even when constrained, youth creates dreams and possibilities.

Ismael Cruz is the founder of Growing Up Wild, a bilingual outdoor education program that primarily serves youth based in Watsonville, California, and strives to help connect youth with nature, build character, and learn about the environment by providing outdoor-based experiential programs that foster socio-emotional well-being and environmental stewardship.

Ismael grew up in San Jose, California, and spent summers visiting rural Mexico, where his parents were born and raised. As a credentialed bilingual teacher, Ismael has taught at Cabrillo College, Pajaro Valley Unified School District, and Santa Cruz County Outdoor Science School. After getting introduced to outdoor education as a counselor for a program called Camp Unalayee, Ismael developed a passion for advocating for the transformational power of outdoor environmental education. Currently, Cruz is an alternative education teacher with the Santa Cruz County Office of Education, and lives on the campsite of Growing Up Wild with his wife and two kids.

What led you to work with young people through outdoor education?

My work in education began at the preschool level. I studied child development in college and became a passionate learner in child growth and development. When I was a preschool teacher, I learned to support the emotional well-being of young children. I realized that getting children outdoors is a crucial part of emotional health.

My first formal introduction to outdoor education was when I became a counselor for four consecutive summers for a program called Camp Unalayee. As a counselor, it was easy to observe the positive impact that outdoor education had on young people, and it left a significant impression on me.

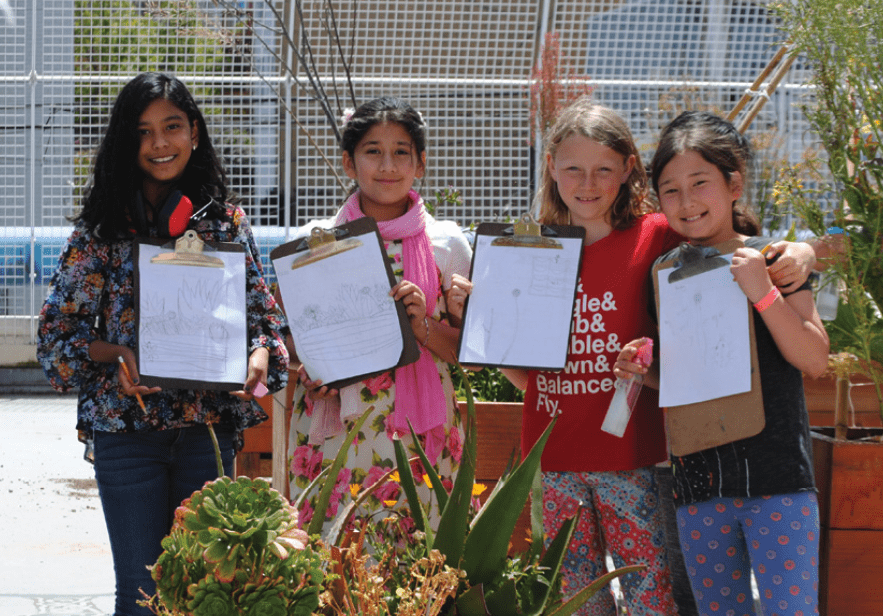

Outdoor education is unique because it connects young people with science, nature, and their peers. Through outdoor education, young people learn empathy by deepening their direct experience of the world around them and fostering relationships with people from diverse cultural backgrounds.

How did you go from this camp counselor experience and teaching into starting Growing Up Wild?

My experience as a camp counselor inspired me to start my own outdoor education program because I wanted to increase outdoor education opportunities for youth and recognized that there was a need for it in my home community.

In 2004, as a first-time homeowner, I purchased five acres of forest land in the Corralitos redwoods 30 minutes from Watsonville. From dropping trees to milling the logs, we built the campground from the ground up. In 2008, a forest fire devastated the area around our home, which served as an impetus for establishing Growing Up Wild. We organized a benefit concert to fundraise money for our neighbors who lost their homes in the fire. A year later, we organized another benefit concert to raise funds to cover insurance for Growing Up Wild’s first year.

The traditional approach to outdoor education is through partnering with public parks and using public lands. What makes Growing Up Wild unique is that we have our own campground which allows us to provide private overnight camping as a part of our programming.

How do your programs like Boys In The Woodz and Girls Paving The Way develop young people through outdoor education? How have you seen it change them and bring out their character and curiosity?

Boys In The Woodz is our flagship program that I have organized for the past 10 years. It builds character, social skills, personal growth, and environmental awareness. Girls Paving The Way is a program that operates in partnership with a number of local community organizations to support middle school girls with the transition into high school. We provide outdoor education for the students while other programs provide things like academic tutoring, mentorship, and college planning.

As part of our programs, young people learn self responsibility, trust, and independence as they must communicate their needs with counselors, and join an unfamiliar setting with new people. Our activities challenge young people to work together in shared leadership and collaborate to problem solve, which demands that facilitators step back to allow youth as much direct experience as possible. As a result, young people increase their understanding about themselves, how they affect others, and the world around them.

How does your work as a K–12 teacher intersects with this work? How do they influence each other? Where do you see similarities or how this builds upon a traditional academic setting?

Anyone who understands the value of education knows the importance of outdoor education. The learning experiences in an outdoor education setting lend entirely to the success of learning in a classroom setting. Students are expected to sit at a desk in a classroom and use their heads. In an outdoor setting, learning is more multidimensional because the content of outdoor education requires that they engage physically, socially and mentally with their environment. Children are, by nature, multidimensional learners, and it is easy for them to feel restless or daydream when in a classroom environment that constrains their focus. It is often easier for them to focus when they are free to use all of their senses and faculties as a part of learning.

I did not necessarily expect the positive response that Growing Up Wild has received from local teachers and administrators. With permission from principals, Growing Up Wild recruits students from local schools where relationships with teachers, families, and students already exist. I came to find out that public school teachers believe in summer camps’ social and emotional value and advocate for my program when they learn that it is an opportunity for their students.

The other part of this is receiving training for Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) as a K–12 teacher. I was launching Growing Up Wild in tandem with learning NGSS, and so I incorporated those standards into Growing Up Wild programming. The NGSS are more conducive to learning in an outdoor setting than the previous standards.

Can you share a little bit specifically about your work at New School in Watsonville? How has outdoor education played into that?

New School is where we created an outdoor education program that lasted four years right up to the pandemic. A veteran teacher working in a small alternative credit recovery high school pushed for a science-based field trip program. Integrating my program with his vision for his students was seamless when he learned about my work. He took care of the administrative work of speaking with school faculty and getting permission from parents. While fostering environmental stewardship, we imparted leadership and problem-solving skills, as well as a renewed excitement for learning. This was particularly inspiring because many of these students were new arrivals from Latin America, former gang members, teen parents, people with disabilities, or identified as LGBTQ+. My background as a Mexican-American helped me connect and build trust with these young people. Through attending my program, these students built a stronger sense of community, built positive relationships with their teachers, which fostered a peaceful campus environment when they returned to school.

Can you speak more on the impact of bilingual education?

Bilingual education was a critical component in my training as a teacher. As a native bilingual and bicultural person, I believe in dual language immersion as an educational model. The goal with Growing Up Wild was to create an immersion program that honored both Spanish-speaking and English-speaking young people. To make young people feel welcome regardless of what language they felt most comfortable speaking, we needed to model a bilingual cultural atmosphere. It was difficult to find fluent bilingual people as camp counselors. I was fortunate to be able to hire my bilingual cousins as camp staff. We set the expectation that meal times would be in Spanish, and gave the English speakers support to understand. We made it clear to youth that they were welcome to speak in Spanish during any point in camp without feeling they needed to explain themselves.

I don’t know if there is an easy solution to living in a community with various languages because identity is so connected to language that if you can’t speak your first language, part of who you are is hidden. It’s a challenge that I can understand very well, and my personal experience with this issue imparts much empathy for these young people.

What do you hope to see in a post-pandemic world?

Growing Up Wild continues on a small scale right now due to the pandemic. We have been around for so long now that word has gotten out about us in the community. In partnership with community-based organizations here in Watsonville and Santa Cruz, we currently lead Zoom calls with youth to engage in virtual activities. We are also forming new partnerships with community-based organizations to expand our reach and capacity. We recently acquired a minibus for taking youth on camping trips and visits to state and national parks. We are raising funds for these trips now.