A majority of Americans are feeling alarmed or concerned about climate change, but many are not sure exactly what this means for their everyday lives, or how this might impact their roles and responsibilities in their professional lives.

For K–12 educators, there is a growing demand for schools and teachers to do more, with parents (more than 80%) and teachers more than 86%, wanting climate change and environmental issues to be taught in schools. Additionally, every school community is already experiencing impacts of climate change (i.e. wildfires, public power shut-offs, poor air quality, high heat days, water shortages, flooding, and transportation disruptions), and are having to navigate the challenges related to these impacts such as disruptions to learn and play and school closures.

Yet, many educators feel overwhelmed or even confused about the realities of climate change, and how to fit this into an already long list of priorities and activities. Other educators express guilt that they are not doing enough, and many others are concerned about the increase in eco-anxiety (or climate despair) in children and youth. The vast majority of educational leaders do not have a clear understanding that they need to be part of the climate leadership landscape. Despite all these challenges, the K–12 education sector has a great opportunity to be a part of the most important teachable moment humanity has ever experienced: surviving and thriving in the climate era.

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report has Serious Implications for K–12 Educators

An important starting point is for education leaders to understand the significance of the most recent findings of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report. This first installment, also known as the “Physical Science Basis” (or Working Group I) was released in early August, and the key findings are stark:

- First, global warming is unequivocally (100% certain) caused by humans.

- Second, the impacts of the climate crisis are already here, and are disproportionately impacting low-income, Black, Indigenous, and communities of color.

- Third, temperatures have already increased by 1.09°C since 1880, and will continue to the 1.5°C mark in the next twenty years due to emissions from past decades.

When taken all together, the teachable moment from these first key findings is about recognizing that humans cannot escape the circular cause-and-effect laws of nature. However, there is one more critical key finding: If humans act urgently, temperatures could peak at that 1.5°C mark and then decline, helping to stabilize the planet and life on it. The teachable moment from this is that anyone who holds any decision-making power in the world right now, has the power to take action and help avoid catastrophe.

It is critical to note that the IPCC Report is extremely credible. It is undisputed by all 195 countries in the United Nations, and by the scientific community. And it ends with a call for immediate action for every country, every sector, and every human – a transformational paradigm shift towards an environmentally sustainable and socially just existence.

An Effective Paradigm Shift Requires All Hands on Deck!

Effective paradigm shifts require engaging all different levers for change, including policy, behavior, and mindset. The K–12 education sector has a hand in all three of those levers of change, with the highest amount of leverage on cultural mindset shifts.

In the past few decades, educational leaders have risen to many challenges. For example, initiatives at the federal, state, and local level seek to address the significant inequalities we face in the K–12 education system in regards to academic outcomes, Additionally, leaders have begun to address the epidemic of trauma in schools, transforming schools into “trauma-informed” environments. Most recently educational leaders have responded to the COVID-19 crisis, which has been a complete overhaul of every aspect of daily life for school communities. The IPCC report calls on educational leaders to now do the same for the climate crisis to protect those most vulnerable to climate impacts, our children and youth.

Similar to COVID-19, to protect and nurture children and youth during the climate crisis, conventional K–12 schooling needs to be reimagined to prevent learning loss and manage risk. Mitigating and adapting to the climate crisis is a core responsibility of school leaders, and communities must put a plan in place that reimagines every single aspect of schools through a lens of sustainability and climate resiliency from campus facilities and operations, to curriculum, to community engagement and overall school culture.

What Educational Leaders Can do to Get Started

Check out the full IPCC Sixth Assessment Report Summary and Overview for educational Leaders, created as a collaborative effort between Andra Yeghoian and thought leaders of the California Environmental Literacy Initiative, which includes a list of top ten actions that Educational leaders can take right now to respond to the key findings in the report. The list ranges from simple to complex, and is organized in a framework for whole-school sustainable and climate resiliency – highlights include:

- Continue to learn about climate change so you can speak fluently on the topic and explain why prioritizing the climate helps to build healthy, equitable, and sustainable school communities.

- Embrace the role of changemaker and integrate sustainability and climate resiliency into your leadership philosophy.

- Invest in systemic change by hiring a sustainability coordinator and/or implementing school and district-wide sustainability and climate resiliency task forces.

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions in campus facilities and operations.

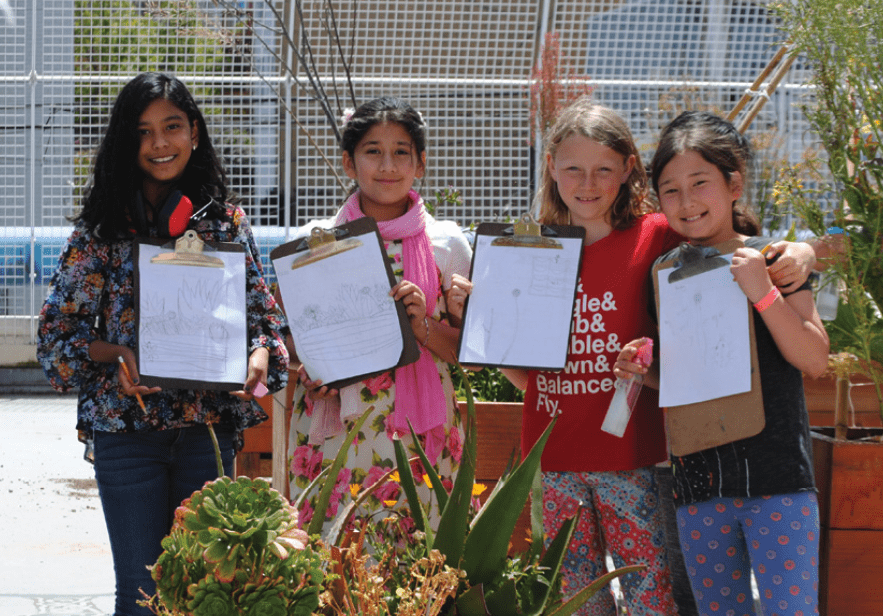

- Integrated lessons and units, as well as opportunities for solutionary project based learning for all students at every grade level.

It is so important that educational leaders see themselves as part of the climate leadership landscape, so that we can build a base of educational leaders who can speak more fluently about the climate crisis, and take actionable steps to help their school communities both mitigate and adapt in the climate era.